When I was at University I loved the study of semantics – how the meanings of words change. I wasn’t too bad at it either and even looked forward to writing a paper on it over the Christmas holidays.

When I was at University I loved the study of semantics – how the meanings of words change. I wasn’t too bad at it either and even looked forward to writing a paper on it over the Christmas holidays.

Unfortunately I fell sick with glandular fever – my throat was so swollen I could only eat soup. Still I shuffled into the library to consult the huge leather-bound Oxford English Dictionary reference volumes. I couldn’t eat, but I could still read! The reference volumes were dusty, heavy, and so big a single one took up a whole desk. I stayed there as long as I could before my sickness drove me back to bed, then I returned the next day. Good job I did, I ended up getting a ‘first’ for that paper!

Semantics isn’t only fascinating to research, it allows you to speculate and gain insight into past societies and human nature.

Take the word ‘fear’ for example. In Modern English ‘fear’ means ‘to regard with fear, be afraid of a person or thing as a source of danger’ and hence involves a subjective experience. However, this meaning did not develop until the fifteenth century (c1460) and previously meant ‘to inspire with fear’, and hence involved an objective experience. The word has therefore experienced a ‘transfer’ of meaning during its development.

Take the word ‘fear’ for example. In Modern English ‘fear’ means ‘to regard with fear, be afraid of a person or thing as a source of danger’ and hence involves a subjective experience. However, this meaning did not develop until the fifteenth century (c1460) and previously meant ‘to inspire with fear’, and hence involved an objective experience. The word has therefore experienced a ‘transfer’ of meaning during its development.

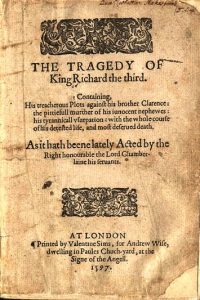

The most likely explanation for this is creativity. It’s in our nature to look for new and inventive ways to express ourselves. By taking the earlier meaning [this or that fears me] and applying it to oneself to create a new way of expressing fright [I fear me], the act of feeling fright comes to be equated with the word ‘fear’. For example, by ‘I fear me he is slain’ (Edward II, IIiv) Marlowe meant ‘I am frightened he is slain’. Repeated use of such a phrase would have resulted in an intrinsic association of being frightened and the word ‘fear’, so that fright eventually became a separate, and eventually dominant meaning. There was no need for this to happen, only our natural sense of creativity meant that it did.

Makes sense, right? Creativity should be a force of language change.

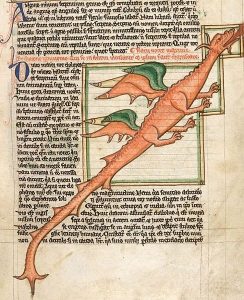

It’s not the only force of change, however. Take the word ‘worm’ for example. The earliest definition of ‘worm’ is ‘a serpent, snake, dragon’, as in Beowulf’s ‘Pa se wyrm onwoc’ (l.2287), as well as in Shakespeare’s:

It’s not the only force of change, however. Take the word ‘worm’ for example. The earliest definition of ‘worm’ is ‘a serpent, snake, dragon’, as in Beowulf’s ‘Pa se wyrm onwoc’ (l.2287), as well as in Shakespeare’s:

Hast thou the pretty worme of Nylus there,

That killes and paines not?

(Anthony and Cleopatra, Vii)

Yet in Modern English this meaning is obsolete and ‘worm’ primarily means:

‘any of various types of creeping or burrowing invertebrate animals with long slender bodies and no limbs, especially segmented in rings or parasitic in the intestines or tissues.’

In addition, somewhere in the ninth century (c.893) the word came to mean ‘any animal that creeps or crawls’, and during the eleventh century, at the same time as acquiring its Modern English definition, it came also to mean ‘the larva of an insect, maggot, grub or caterpillar, especially one that feeds on and destroys flesh, wood, fruit, cereals, etc’. The kinds of semantic change going on here involve ‘generalisation’ (an extension of meaning), ‘specialisation’ (a narrowing of meaning) and ‘transfer’ (a transference or meaning between two or more referents).

In the first place, the meaning of ‘worm’ was clearly ‘generalised’ by having the restricting features of the word’s definition reduced. Instead of referring to specifically named creatures (ie. serpents, snakes and dragons), these specifications were extracted and the definition was extended to refer to any creeping or crawling animal. Thus the word experienced the process of ‘generalisation’.

In the first place, the meaning of ‘worm’ was clearly ‘generalised’ by having the restricting features of the word’s definition reduced. Instead of referring to specifically named creatures (ie. serpents, snakes and dragons), these specifications were extracted and the definition was extended to refer to any creeping or crawling animal. Thus the word experienced the process of ‘generalisation’.

However, the referential scope of the word was then narrowed by adding the feature of ‘invertebrate’ to its definition, thus ‘specialising’ the word into a different more specific sense. ‘Worm’ no longer referred to any animal, but again to special (though different) type of animal, and hence experienced ‘specialisation’.

Finally the additional ‘larva’ meaning of ‘worm’ was developed through association between the common features of these two referents. The appearances and movements of (what we know now as) larvae were observed to be so similar to those of worms that the word was used (for a time) to refer to both. In this way the meaning of ‘worm’ was ‘transferred’ from one referent to another, from worms to larvae.

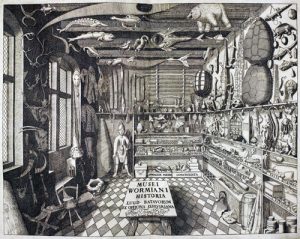

These semantic changes are most likely explained not by creativity but by the English language’s lack or excess of words at any one time to describe the creatures involved. Changes in English society, particularly developments in the growing discipline of biology, would have created a need for new words to describe different creatures. The language would not have been refined enough to already have naming words for all of earth’s animals (just as ‘blue’ is the last colour societies generally name). So, until borrowing from another language or making up the appropriate new words, ‘worm’ was used to refer to all creepy-crawly type animals.

These semantic changes are most likely explained not by creativity but by the English language’s lack or excess of words at any one time to describe the creatures involved. Changes in English society, particularly developments in the growing discipline of biology, would have created a need for new words to describe different creatures. The language would not have been refined enough to already have naming words for all of earth’s animals (just as ‘blue’ is the last colour societies generally name). So, until borrowing from another language or making up the appropriate new words, ‘worm’ was used to refer to all creepy-crawly type animals.

When such words as lizard, dragon, serpent and caterpillar, and later larva, were eventually adopted from other languages ‘worm’ was replaced. It was no longer needed to refer to all creepy creatures, only for worms. It was also no longer needed to refer to ‘larva’, since this word was soon introduced into the language from Latin.

Where creativity comes back into play, however, is with the word’s developed meaning of ‘insignificant or contemptible person’. Similar to such words as ‘dog’, ‘bitch’, ‘pig’ and ‘cat’, ‘worm’ can be used to describe someone seen as having worm-like characteristics or tendencies (ie. being slimy and destructive). Thus as Philip Sidney wrote metaphorically in ‘Arcadia’:

O Clinias,… the wickedest worme that ever went vpon two legges.

(IIIxiii)

‘Worm’ can also be used in relation to certain emotions, and has developed the meaning of ‘a grief or passion that preys stealthily on a man’s heart or torments his conscience’. Hence ‘the worm of [my] conscience’ is used figuratively by both Chaucer (Doctor’s Tale, l.280) and Shakespeare (Richard III, Iiii l.222).

Such developments again have involved ‘transfer’ of meaning: from worms to mankind and their emotions. But this time the process depended on figurative expression rather than association of concrete common features (as with the transfer of meaning between worms and larva). Men, or their emotions, do not actually look or move like worms, yet through metaphor came to be compared to worms in an abstract, figurative sense. Someone somewhere consciously coined the metaphor to illustrate the (slimy, destructive) characteristics of a certain person or the (burrowing) actions of a certain emotion. Then, through repeated use by others, the metaphor ceased to be figurative and became a permanent alternative meaning.

The motivating factor in this case was therefore most likely to be the desire to express things figuratively, rather than the need for new words. Society did not need a new word to describe a contemptible person, but welcomed the opportunity to have a new and figurative way of saying so. Why? Because being creative is part of human nature. Our creativity solves problems, imagines new and useful objects, dreams up concepts, technology and experiments and… drives changes in the development of our language.

I fear me the worm.

I fear me the worm.

I’m afraid of the dragon.

Every time we choose to use a word we define and redefine its meaning. The power is ours!

What words have you used, or embraced using, in a new and inventive way lately?

Great post Zena! Really enjoyed this. I envy your education in semantics – I’ve always found the stories behind words fascinating

Just today, I wanted to use ‘shamble/shambling’ to describe the awkward gait of some zombies in my story and I came to wonder how that was related to the shambles that characterises my writing desk?

Well, nowadays shambles is a general confusion, which likely arose in the early 20C to describe ‘the destruction after a great battle’. This sense drifted through a bunch of meanings over the centuries, from ‘a scene of carnage’, from ‘a butchery’, from ‘a place where meat is sold’, from ‘the bench where the meat was butchered’ (called a ‘shamble table’ after the 14C or schamil early 14C), all from the OHG scamel ‘stool’, ultimately from the Latin scamillus for low stool .

And the shambling gait of my zombies? It bypassed the whole butchery business and harks back to that original table – it was a word used to describe the awkward gate of someone who walked with the bow-legged, wobbly gait characteristic of the splayed legs of a bench (or maybe it’s from the splayed posture of someone sitting astride a low bench). The French word for bow-legged and wobbly/rickety is bancal for the same reason. Which reminds me of the link between rickets and rickety. 🙂

Anyhow, I’m procrastinating now. Must get back to my shamble table and butcher some more words!

I love your shambles research, Rob! I can just see the destruction after a great battle in those terms. Awesome! Thank you for stopping by and sharing that with everyone. You rock! Now, back to your shamble table with you!

I am braindead from work stress/illness/lack of sleep, so unable to think of any words I’ve been messing with (although I could tell you a few Boris Johnson has been messing with!), but what a fabulous post! I do love language geekery, and really like the way you link it all in with creativity. 🙂

Thanks for stopping by, Liz!! I’m glad I could improve your day somewhat! I love word nerd stuff too. In fact, I might just write another post on the subject… Watch this space!